The legal profession is dominated by smaller firms, it is a demographic made up of suburban, rural and regional practices servicing local communities, and boutique firms.

Law firms face lifecycle and generational-change issues in which sale, succession and partnership pathways are options.

We spoke to Peter Frankl, a specialist in law firm practice broking and valuations, about what lawyers should consider when selling their firms and what buyers should look for. Peter Frankl also edits news website Legal Practice Intelligence.

Advice for sellers

“For sellers, the key is to stay in control of the process,” said Peter. “Decide what type of buyer would benefit most from buying the firm. Prepare information about your firm with those types of buyers in mind. Release information in stages so that you can obtain some feedback at each stage and decide whether negotiations are worth continuing. Without a methodology in place before getting started, the process of selling a practice can be time consuming and emotionally draining.

“An experienced broker of legal practices can be a source of advice on valuation and can put in place a methodology that protects privacy and confidentiality.”

Advice for buyers

For buyers, Peter advises a focus on revenue rather than expenses.

“The value in a firm is mostly in its revenue,” he said. “This means understanding fee revenue by areas of law. Different areas of law will have different degrees of attractiveness to a buyer.”

Other data points to consider include the number of matters opened each year and the average value of those matters.

“Expenses and staffing are most relevant when there are impediments for the buyer to optimise them in the future – for example, a long uneconomic lease on premises."

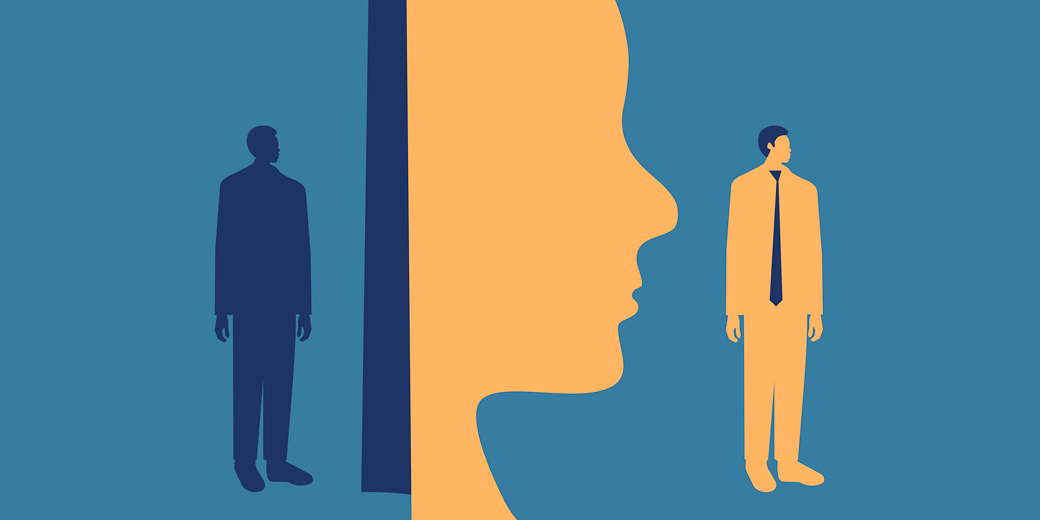

The ideal buy-out scenario usually involves the outgoing principal staying connected to the practice on a flexible reduced-time basis.

“In the eyes of clients, the change in ownership is seen as a positive expansion with the introduction of new people, skills and services. It can be risky to present the image of ‘under new management’ with the disappearance of the outgoing principal.”

Then there’s the matter of money

“There are wildly different views on the price and value of legal practices. This can be explained by the fact that not all firms are of interest to all buyers. An obvious example is that a conveyancing firm will be of little or no interest to a family lawyer. Therefore, there has to be a ‘match’ in interests. When there is a good degree of compatibility between the firm and the prospective buyer, the value to the buyer becomes evident. Because the amount that is usually required to buy a law firm is relatively modest compared to the value of residential property in the big cities and also compared to other types of businesses, the most common scenario is a single lump sum payment.”

Peter encourages lawyers to consider buying a practice over setting up their own.

“Buying a practice is a booster strategy. It can save you years in getting to where you want to be. Consider how much time and money you would spend on advertising and business development for a new practice, just to reach the same level of revenue that you get with an existing practice. A dollar spent on buying a practice will generally have a much better return than a dollar spent on advertising.”

Further, it is at present a comparably inexpensive proposition with a manageable downside.

“At the moment, the funds needed to buy a legal practice are many times less than required to buy most other businesses. Should you later want a change in direction, or if the practice doesn’t generate enough income, it is unlikely to be a financial catastrophe. Even if you close the doors and walk away, if you have managed your exposure to the few fixed costs of running a firm, you will survive a change of direction.”

In addition, running your own practice brings the benefits of autonomous decision-making and freedom from dependency on a salary.

“If you have an unexpected parting of the ways with your employer, it is a certainty that your income will go from whatever it is now to zero. If you lose a client, then your income may dip by a small single digit percentage and that is if the lost client isn’t replaced by a new one.”

![How to handle Direct Speech after Gan v Xie [2023] NSWCA 163](https://images4.cmp.optimizely.com/assets/Lawyer+Up+direct+speech+in+drafting+NSW+legislation+OCT232.jpg/Zz1hNDU4YzQyMjQzNzkxMWVmYjFlNGY2ODk3ZWMxNzE0Mw==)